Shapiro and lawmakers seek to erase medical debt

Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro proposed $4 million in his 2024-25 budget to cancel medical debt.

When Kris McConnell and her husband needed emergency surgeries last year, they were confident they had good insurance and didn’t think twice about getting the help they needed following a car accident and to treat severe gastrointestinal issues.

Then the bills started coming in for the central Pennsylvania residents. Now they owe about $13,000 in medical debt — and that will likely increase because McConnell, 59, just had to go to the hospital after she fell.

“His surgery was almost $86,000,” McConnell said of the cost of her husband’s surgery without insurance. “Who in their right mind can pay that? If you didn’t have insurance, and you had no extra coverage? Holy moly, that’s buying half a house or buying a vehicle — two vehicles. You know, we were just shocked.”

While they’re certainly relieved they don’t have to foot the whole bill, the $13,000 in debt they do have is more than they can afford right now. McConnell said she’s avoiding nonemergency health care because she’s worried about mounting costs.

“So that means what? My health gets worse because I can’t get the proper medical treatment, can’t get the medication,” said McConnell, who has suffered from severe gastrointestinal issues for years. “So you’re kind of hanging in the air.”

McConnell is definitely not alone when it comes to medical debt. Nearly one in three adults in the United States are struggling with unpaid medical bills. In Pennsylvania, approximately 1 million people carry medical debt, and rural residents are hit especially hard due to a larger portion of the population being uninsured, higher unemployment rates, and longer travel times to medical specialists. That longer travel time means people may put off seeking health care because of the time it takes, leaving their condition to potentially worsen and become more expensive to treat. For example, 21% of residents in Warren County, a rural area in northwest Pennsylvania, hold medical debt, according to the Urban Institute, a left-leaning think tank based in Washington, D.C.

Medical debt is a leading cause of bankruptcy in the U.S., and residents with medical debt, health care providers and lawmakers told the Pennsylvania Independent that the high cost of unpaid medical bills can deter people from seeking further health care.

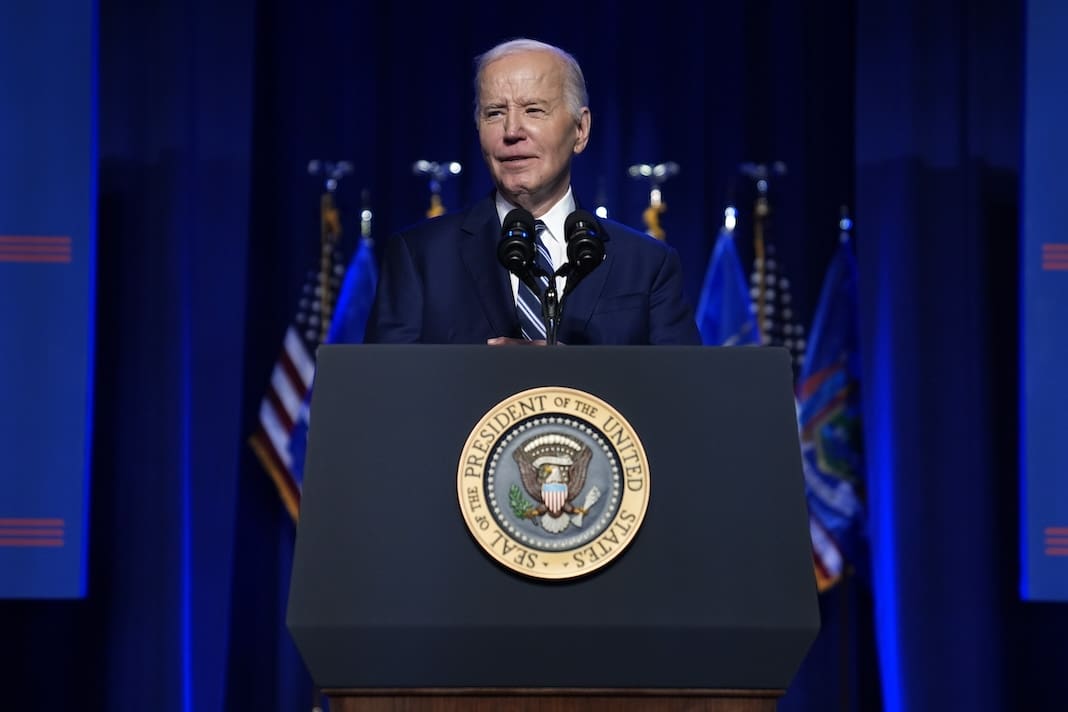

To address the debt crisis, Democratic Gov. Josh Shapiro proposed allocating $4 million in his 2024-25 budget to erase medical debt for some Pennsylvanians. The plan, which mirrors legislation introduced by Democratic state Rep. Arvind Venkat and passed by the Democratic-led House last year, would direct the state to contract with debt relief nonprofits that would buy Pennsylvanians’ medical debt. Because medical debt buyers can purchase the outstanding health care bills for pennies on the dollar, Shapiro estimates that a $4 million state investment could cancel as much as $400 million in debt.

After a patient does not pay a health care bill, the provider, such as a hospital, can try to collect the debt on its own or sell it to someone else. That debt can be sold for so little because it’s rarely fully collected. With an incredibly low sale price, that means the for-profit that purchases the medical debt can often make money even if it only gets a fraction of what’s owed, and the provider receives some money without having to pursue legal action.

Residents would qualify to have their medical debt erased if their annual income is 400% of the federal poverty limit or less, which amounts to an annual salary of $60,240 for a single person or $124,800 for a family of four. Residents would also be eligible if the amount owed is at least 5% of their annual income. Pennsylvanians would not have to apply for the relief; rather, a vendor selected to oversee the program would inform the individual after their debt is purchased and thereby eliminated for them.

State law stipulates that Pennsylvania lawmakers have until June 30 to pass a state budget, though legislators have not met that deadline in the past. Federal law mandates that state employees must continue to be paid even if there is no budget, but other programs can face cuts. In 2015, for example, pre-K programs and domestic violence shelters closed temporarily because the budget was not passed until several months after the deadline.

“As I’ve traveled across the commonwealth, I’ve heard firsthand from Pennsylvanians who are struggling with high costs — including those being crushed by medical debt,” Shapiro said in an April 2 press release. “Erasing medical debt is a practical, commonsense way that we can deliver real relief for folks all across Pennsylvania.”

Pennsylvanians’ mounting medical debt stems from what Democratic state Rep. Tarik Khan said is a health care landscape in the state and across the country that leaves people with unequal access to care, low-wage jobs without health insurance benefits that render residents unable to afford medical care, unaffordable deductibles, high prescription drug costs, and long transportation times to emergency care in the wake of hospital closures, among other issues.

“For the vast majority of people, if one thing goes wrong, they can very quickly be on the wrong side of medical debt,” said Khan, who also works as a nurse practitioner and was a prime sponsor of Venkat’s medical debt legislation. “And so this [Shapiro’s proposal] is just going to free people up to seek medical care and to take care of themselves.”

It’s not solely medical care that residents would be able to afford if their debt were erased, health care providers said. Dr. George Garrow, the CEO of Primary Health Network, told the Pennsylvania Independent that patients face a long list of excruciating decisions in the wake of accumulating medical debt.

“They sometimes have to make a difficult choice about paying down their medical debt or paying rent, or paying down their medical debt and buying food, or paying down medical debt and continuing their education,” said Garrow, who earlier this month appeared at a press conference with Shapiro to speak about the benefits of erasing medical debt.

Garrow’s organization works with rural and low-income residents at 50 health centers in Pennsylvania and northeast Ohio and is the largest federally qualified health center in the commonwealth. Garrow noted that their patients typically accumulate medical debt from emergency room visits while uninsured or underinsured.

Venkat, who practices as an emergency physician with Allegheny Health Network, said health care providers would also be deeply relieved to see their patients’ medical debt erased. If that happens, residents may be able to access more timely preventive care. Waiting to access care because a person is worried about the cost can translate into worsening medical conditions — and for some patients, that means waiting so long that their disease is no longer treatable, Venkat said.

One such patient came to Venkat with back pain. It turned out she had breast cancer that had spread throughout her body.

“When I spoke with her about it, she told me that she had medical debt and that she was fearful of additional medical debt and that led her to not seek care until, frankly, it was too late,” Venkat said.